The Neuroscience of Taming the Wandering Mind

Posted originally at ScienceNonfiction Blog, edited and reviewed by Public Communication for Researchers.

Have you ever tried sitting still and relaxed for three minutes, and focusing on a simple thing? You can focus on a familiar name, a simple image, a small nearby object, or a sensation like breathing. If other thoughts, feelings, or sensations come up, gently ignore them and return your attention to the initial thought.

A young monk meditating in the forest (image from Wikimedia Common)

How long are you able to focus? How many distractions come up? Kudos if you can hold the thought with no distractions for more than a few seconds. Most of us can’t. Thoughts naturally pop up in our minds, whether we like it or not. If we can slow the stream of thoughts, we can focus better (and hence be more productive). One way to do this is by practicing mindfulness.

The American Psychological Association defines mindfulness as “moment-to-moment awareness of one’s experience without judgment.” There are many mindfulness practices, such as yoga, tai chi, and relaxation therapies. Mindfulness can be promoted by practices like mindfulness meditation. A brief and common example of mindfulness meditation practice is the three-minute exercise described earlier.

Many varieties of mindfulness meditation affirm that it is possible to train our minds to become more aware of our thoughts, to tune out distractions, and to become better at focusing both during meditation and in everyday life. Although many claims about the benefits of mindfulness meditation are anecdotal and not yet substantiated, there is scientific basis for some of its benefits. Some of the empirically supported benefits of mindfulness include stress reduction, cognitive flexibility, and boosts to working memory.

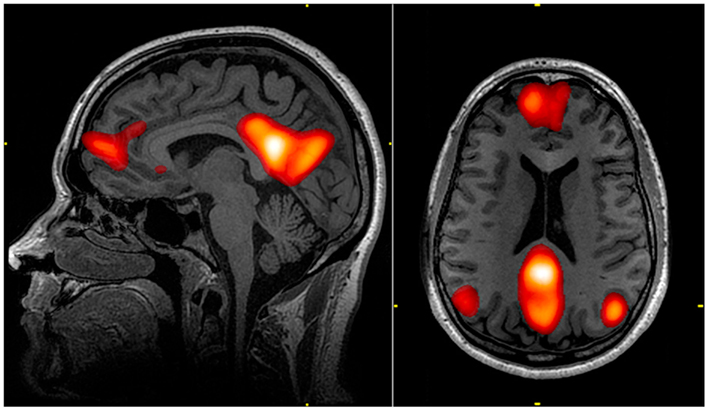

To understand how mindfulness meditation works, let’s delve into the basic neuroscience behind brain wandering. While awake and not focusing on the outside world, our brains are constantly in a wandering state. Using a popular brain imaging technique called fMRI, scientists have found that the primary areas of brain activity of this wandering state can be simplistically separated into hubs that are broadly responsible for emotion about ourselves and others, autobiographical memory, and future simulations. Unsurprisingly, we gravitate to those kinds of thoughts when we try not to think. These regions are also associated with anxiety, depression, and addiction.

A fMRI of the side (left) and the top (right) views of the “wandering” network in human brain. The hubs roughly correspond to areas responsible for emotion, memory, and decision-making. (image from Wikipedia)

In contrast, during the three-minute mindfulness practice, our brains tend to activate areas that form the “Task-Positive Network” (TPN), which is broadly responsible for directing our focus to both sensation and memory. By activating TPN, we can become more aware of our breathing, conversation, or any other internal and external stimulus. As the TPN becomes more activated, our brains wander less and become less activated. Essentially, mindfulness meditation leads to increased activity in TPN and decreased activity in the wandering network. For longer-term meditators (years to decades), research shows more profound changes in both brain structure and behavior.

One way to test those changes is the motion-induced blindness test, in which participants focus at a stationary dot with a moving background, until some or all of the other stationary dots seem to disappear. On average, ordinary people maintain a ‘blindness’ state for around 3 seconds. In a 2005 experiment, Buddhist monks who have practiced meditation for 5 to 54 years maintained this for 4.1 seconds while the most experienced meditator maintained the illusion for more than 12 minutes. This is one of many experiments that showed that meditation practitioners can focus more easily.

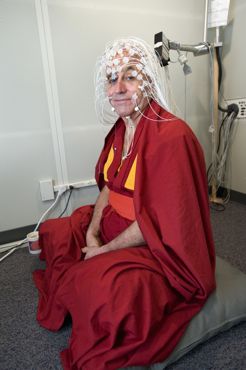

A Buddhist monk, Matthieu Ricard, in a meditation pose wearing a sensor net for measuring brain activity. (image from WISC)

This all sounds fascinating, but it should be taken with a grain of salt. Research in this area has a lot of challenges, such as reliance on self-reported progress and the placebo effect. A review of 124 published trials on mindfulness, and 36 systematic reviews found evidence of reporting bias (e.g., under-reporting undesirable results). A step towards fixing these problems is to use randomized longitudinal studies with large sample sizes. However, there is still consensus in the scientific community that mindfulness meditation can positively change our brains.

If you found yourself switching to email or Facebook halfway through this piece, don’t worry – mindfulness is a skill you can learn. Research suggests a mindful mind is often a happy mind. If you want to get started, try watching one of these many TED talks (including one given by the monk shown in the above picture) or one of the many mindfulness apps. Start small, keep practicing, and in a few years, maybe three minutes of focus will be easy – and you may find yourself more efficient, happier, and perhaps more spiritually fulfilled.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: